Saint-Martin Church of Maizières-lès-Metz: A Modernist Vision in Concrete and Light

The Church of Saint-Martin in Maizières-lès-Metz is a modernist landmark of concrete and light. Rebuilt after WWII, it became my quiet obsession: after months of locked doors, I finally stepped inside to discover its brutalist beauty and the dramatic play of shadow and light.

I never thought getting into a church would turn into such a game of patience. The Church of Saint-Martin in Maizières-lès-Metz isn’t far from where I live, so I kept stopping by with my camera, but every time I went the doors were locked. That’s probably why it became a bit of an obsession — the more I couldn’t get in, the more I wanted to.

I live not far away, so I began going there early in the mornings. In winter, I’d wake up before dawn, step into the fog, and walk with my camera hoping the weather would gift me something otherworldly. Each time I arrived, though, the doors were shut. The church only opens for Mass, and I didn’t want to intrude during service. Emails to the parish went unanswered. So, for months, I circled it like a moth — capturing only the rough exterior walls, the massive wooden beams, the copper roof.

Rebuilt after the destruction of the Second World War, this church is a striking example of post-war modernism in religious architecture. Designed in the late 1950s by Jean Rouquet and his team, the building embodies a style sometimes described as belonging to the “school of Le Corbusier”—with its raw concrete surfaces, bold geometry, and emphasis on the interplay between light and shadow.

Saint-Martin is not a single structure but a whole parish complex. It includes the main church, which seats around 720 people, a smaller “winter chapel” for 120, a baptistery, sacristy, parish rooms, and the presbytery. From the outside, its concrete and wood construction gives it a rugged, almost sculptural presence. Step closer and the details reveal themselves: walls coated with rough plaster, beams left bare from the formwork, and a copper roof supported by laminated timber.

Then one day, by sheer luck, I was walking back from the city centre and passed the church again. The doors looked as firmly closed as always, but a man was stepping out. I asked him if it was open. “Yes,” he said. And suddenly, after so many failed attempts, I was inside.

What surprised me most is how the doors give nothing away. From the street, you would never guess there was even a service happening. I slipped in at the very end, found the woman in charge of closing up, and explained my strange little quest. She was wonderfully kind. I had no camera with me but she agreed to wait while I sprinted home. Ten minutes later, breathless and sweating, I returned with gear in hand.

And then came the reward. An empty church, no people in the frame, and the freedom to play with the light. The woman even turned lights on and off for me so I could experiment. Inside, the architecture is a theatre of shadow and light: the nave half-dark, the altar glowing under a vast wall of glass, the ceiling beams exposed like ribs.

Inside, the design plays constantly with contrasts. A vast wall of glass in the choir floods the altar with southern light, while the nave remains half in shadow, illuminated only by narrow strips and coloured windows high on the walls. This creates what the architects called an “encounter between shadow and light,” turning the liturgy itself into a stage where sacred gestures stand out against a backdrop of shifting brightness.

The baptistery, placed at the lowest point of the church, is accessible directly from outside, recalling the ancient rule that the unbaptised should not yet enter the sacred space. Above it, the weekday chapel opens onto the main choir, physically linking daily ritual with the heart of the parish.

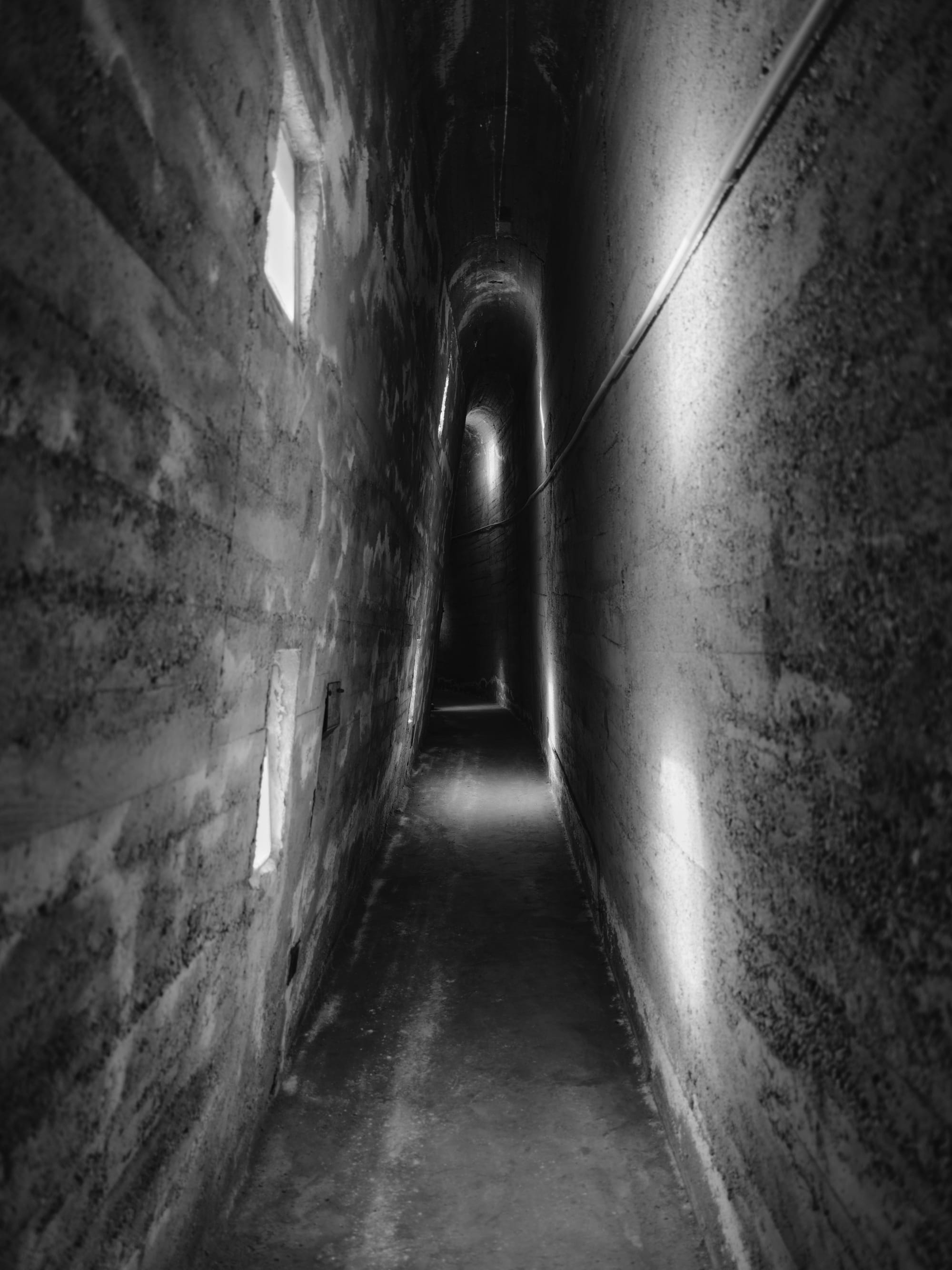

I also discovered something I had only read about before: a discreet passage running behind the sanctuary, linking the altar space to the weekday chapel and sacristy. It is hidden from most eyes, a backstage corridor where the daily workings of the parish quietly unfold. Seeing it felt like peeking into the secret anatomy of the building.

You might quickly notice similarities with Le Corbusier’s famous Chapel of Notre-Dame-du-Haut at Ronchamp: the curved apse wall, the thick concrete pierced with light-giving openings, and the theatrical use of daylight. Yet Saint-Martin is no mere imitation. Where Ronchamp floods its nave with mysterious shafts of light, Maizières channels brightness more strategically, keeping the nave subdued so that the altar, bathed in sunlight, becomes the dramatic focus.

Over the decades, Saint-Martin has undergone practical changes: new flooring to prevent slips, adaptations for heating, even the replacement of its cross. But the essence of the building remains. Its unclad concrete, once shocking in its austerity, now speaks of the optimism and experimentation of a generation rebuilding from war.

Walking inside today, you find no medieval frescoes, no baroque statues. Instead, you encounter a raw architecture meant to free the imagination, allowing each visitor to discover meaning in stone, wood, and light. It is a modern sacred space—severe, luminous, and deeply human.

Practical information